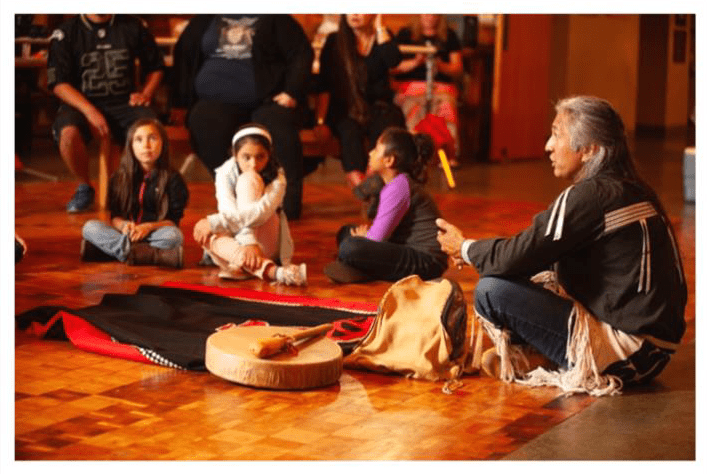

Figure 13. Native people performing a traditional dance

Impacts

“We have the capacity to heal if we have the right structure and supports. We don’t have to hide it.”

–Aaron Payment, EdD, EdS, Med, MPA (Sault Tribe of Chippewa Indians).

Highlight: Road To Healing

As the Road to Healing Reports are released, it is important to note that retraumatization may occur in your communities. Health care providers, tribal administrators, and educators should be prepared for potential influxes of patients, students, and community members in crisis. Increase staff trained in trauma-informed care during the days and weeks surrounding the release of the Road to Healing Reports and encourage staff to practice self-care while assisting community members in crisis.

The first step toward change is awareness. Right now, the public-education system acknowledges neither the U.S. government’s acts of genocide nor its policies of forced assimilation (National Congress of American Indians, 2019). The upcoming Road to Healing report, commissioned by Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, will be an important step to engaging with this history and addressing its continued influence on the AI/AN population. But it is only the beginning. A new wave of stories of abuse from the survivors of Indian boarding schools and their descendants have already emerged from the report’s initial listening sessions (Rickert, 2023).

Acivities:

Reflection Questions:

- Do I provide space in my practice for my clients/students to be the experts in their own histories?

- Have I created a support system to help me navigate the emotions that come up for me when I am learning about intergenerational trauma and harmful policies created by my country’s government?

- Do I look for AI/AN ways of knowing and AI/AN scholars when I am seeking out information to better support my AI/AN clients/students?

Dancing

Traditional dancing can play a significant role in healing from intergenerational trauma. Interwoven with history, spirituality, and community, traditional dances offer a path toward reconnecting with one’s root and fostering emotional and psychological well-being. Traditional dancing serves as a powerful tool for healing in several ways:

- Cultural reconnection: Participating in these dances helps individuals reconnect with their culture, providing a sense of identity and belonging.

- Spiritual connection: Dancing allows participants to connect with their spirituality, offering a sense of purpose, inner peace, and a way to address the spiritual wounds inflicted by historical trauma.

- Community support: Traditional dancing is a communal activity and fosters a support system where individuals can heal collectively, share their stories, and receive emotional support from one another.

- Resilience building: Dancing requires discipline, commitment, and perseverance, and can serve a vital role for healing from trauma as practitioners build resilience and develop a positive self-image.

Is there an opportunity to integrate traditional dancing into your practice, office, or classroom? Are there community events or clubs in order for community members to connect with this integral part of AI/AN culture and community?

Resources

Qungasvik: A Model for Promoting Reasons for Life and Reasons for Sobriety in Yup’ik/Cup’ik Communities created by the Center for Alaska Native Health Research.

Resilience and Brilliance

The U.S. government has tried for more than 500 years to erase the history and culture of the AI/AN people. Currently, it recognizes 574 different tribes in the lower 48, Alaska, and Hawaii, while states recognize an additional 200. Almost all of the people from these tribes are now English-speaking Americans, but even after a cultural genocide they remain Native, with unique and resilient languages, cultures, and traditions. The resilience of these tribes comes in part from three things: language revitalization, cultural reclamation, and traditional and contemporary art.

Language Revitalization

Congress knew early on that language was an important part of how Native people identified with their culture (Indian Education, 1969). By forcing children to speak only English, and punishing them for speaking their language, many children lost their Native language. The U.S. government implemented these strategic measures to force assimilation and make it easier to take AI/AN people’s land away—the places where they spoke their Native language. However, today, 350,000 people speak more than 175 AI/AN languages in the U.S. More than 170,000 people speak Diné Bizaad (Navajo) alone. (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011).

While many Native languages persist even after the attempts to eradicate them, many are now lost or spoken by only a few tribal elders. Every year more tribes work on reviving and restoring their languages and now the U.S. government is supporting these efforts. The Biden Administration is working on a 10-year plan to revitalize AI/AN languages in the U.S. and many tribes are already bringing language back using old recordings from anthropologists and input from linguists.

The reports from Congress in the 1800s were right—language is a huge part of Native Americans are as people. AI/AN languages are more than just a tool for communication, they are a container for thousands of years of identity. They transmit a unique worldview and culture.

Highlight: Native Language

Tribal communities with many Native language speakers have lower suicide rates (Ozbolt) and tribal communities with language and cultural education programs have higher high school graduation rates (Meza). Speaking a unique language, and being a part of bringing them back, builds culture as a tribe. And the resilience in preserving and revitalizing language is a big step toward healing from trauma (Marshall, Antoine).

Acivities:

Reflection Questions:

- Have I asked my clients/students about their preferred language?

- Have I checked my bias and reactions to clients/students who don’t speak “perfect” English?

- Do I see speaking multiple languages as a strength and understand the importance of cultural connections?

- Do I know of language programs in my community that support AI/AN language learning?

Ceremony

“The most powerful forms of healing are wrapped in ceremony.” – John Bird (Blackfoot) Substance Abuse & Suicide Prevention Facilitator.

Ceremonies are not mere cultural practices; they serve as a crucial pathway toward healing, reconciliation, and restoration of identity and spirituality for AI/AN people. They help reconnect individuals with their culture, facilitate storytelling and spiritual connection, provide a supportive community, and promote emotional expression. Whether it is the sweat lodge ceremony, the powwow, or the potlatch, these practices reinforce the importance of cultural identity and serve as a powerful antidote to the erasure of the boarding school system. As community leaders and providers, you have a unique position to facilitate intergenerational connection and cultural knowledge sharing. Are ceremonies practiced in your community? Which ones, and who leads them? Do young people have access? Is there a community calendar that lists seasonal ceremonies? Work with your community to create these resources, and they can have powerful impacts.

Cultural Reclamation

Forced assimilation and removal destroyed cultural practices as effectively as it did language, but AI/AN people in the U.S. displayed remarkable resilience for preserving lifeways in the face of this radically changing landscape.

First foods were an important connection to culture for many tribes, but these relationships were also destroyed by colonizers. The U.S. Army intentionally culled the buffalo herds of the Plains tribes (Waltmann, 1971), Western agriculture destroyed camas bulb fields, and overfishing destroyed many salmon runs (Thompson, 2022). But many of these relationships are healing. Salmon ceremonies, once common in coastal and river tribes, are coming back again. Buffalo herds are repopulating in the Plains. The federal government is beginning to involve tribes in the management process for wildlife habitat, forests, and wildfire management. Relationships to plants and animals that tribes have held since time immemorial are being recognized, and those relationships build back lost culture, community connection, and physical health.

Figure 14. Native youth listening to an Elder’s story

Traditional and Contemporary Art

The patterns and colors of Native art have featured in mainstream colonizer culture since the first European contact. Centuries later, traditional arts like weaving, beading, and sewing have continued to be unbroken. For many people, they are a physical connection to tradition and culture, and many tribal communities teach these skills both to strengthen tribal bonds in youth and as a path to healing.

Dance, song, and craft are often combined in traditional Native art. In the 1970s and 80s, a circuit of traditional and competitive powwows grew across the nation (Lassiter, 2005). Now, there are hundreds of intertribal powwows every year, where AI/AN people from hundreds of tribes perform expressions of traditional culture—such as the jingle-dress dance of the Navajo Nation—and explore new evolutions of the arts. More recently, Native culture—not just the appropriated imagery—has begun to be featured in mainstream media. Artists like The Halluci Nation, who blend traditional Cree singing and dancing with modern beats, are trending on Spotify.

Their music videos, which have millions of views, portray modern Native people engaged in traditional dance, and often tell stories about the challenges faced by their communities. Other popular music artists like Supaman, Tall Paul, and Snotty Nose Rez Kids are blending AI/AN culture with hip-hop elements, building a new, shared identity in urban Native populations. Contemporary art also helps AI/AN people heal from historical trauma. Popular television shows such as Spirit Rangers, Molly of Denali, and Reservation Dogs put young AI/AN actors in front of a national audience, the latter offering a highly visible portrayal of the horrors of the residential school system. Such representation builds collective understanding both of the nation’s oppressive history and how it created the contemporary reality for AI/AN people, knowledge crucial to any eventual healing.

Activities: Reservation Dogs: Deer Lady – Discussion Guide

Reservation Dogs: Deer Lady – Discussion Guide

Season 3: Episode 3

How to use this guide: The questions below are meant to serve as prompts, not a script. Please feel free to change the language to best suit the participants in your group. We also encourage you to follow the natural flow of the conversation and only bring in additional prompts when the discussion seems to be losing steam. Please be mindful of any stress or trauma reactions AI/AN participants may be experiencing. The goal of these discussions is to move from being trauma-informed to healing-centered.

“They can’t stop you from smiling.” – Deer Lady

Deer Lady

- What do you already know about the Deer Lady (or Deer Woman) legend?

- Why do you think the writers felt that Deer Lady should be in this episode?

- Why does Bear stay safe during his time with Deer Lady?

- Did Deer Lady’s actions right a wrong? Why or why not?

General Prompts

- What emotions came up for you while watching this episode?

- What stereotypes were confronted in this episode?

- What did you learn about the role of the priests and nuns at the boarding schools?

- Why did the priest tell Deer Lady that “Most men who live like me are dead by now?”

- What questions do you have after watching? Where can you look to get those questions answered?

Prompt for Discussions with AI/AN Peoples

- In what ways can this type of media help us heal?

- What are the benefits or risks of bringing these hard conversations to more mainstream audiences?

Figure 15. Full waiting room at a Native health clinic

Frameworks for Healing

AI/AN tribal communities have long practiced community-based and traditional healing. As health care became increasingly tied to the Indian Health Services’ standards of care, however, traditional healing practices became deemphasized. That process, however, is beginning to reverse itself. Congress has authorized more flexible sorts of funding, so tribal nations are increasingly applying traditional healing practices to modern ailments under a self-governance approach. As tribes are at varying stages of cultural and traditional reclamation, these traditional practices may be applied to a wide range of physical, mental, emotional, social, and spiritual matters.

The 2015 Tribal Behavioral Health Agenda aimed to measure the impact of trauma-informed care and tradtional medicine on health outcomes (SAMHSA, 2016). Traditional practices and ceremonies are important sources of healing for many AI/AN people, despite the complex task of integrating them with modern practice. As researchers gain familiarity with a trauma-informed framework, however, new strategies have begun to emerge. Whatever the specific methods, any effective trauma-informed care begins with the reclamation of culture, language, and AI/AN ways of knowing.

Traditional Medicine Approach to Healing

While traditions vary widely across AI/AN communities, one common thread is how all healers are called to lifelong learning and practice in traditional medicine. Not only must they be steeped in culture and language, they learn to seek direction from their ancestors, as holistic herbal medicines are often passed down through the ages via oral tradition. In some cases, the physical form of these medicines is crucial, such as how some forms of aspirin were derived from an Indigenous practice of using red willow bark as medicine. Anishinabe (Ojibway, Odawa, Potawatomi) Biimaadziwin teachings include stories of Nanabush and Ducks to explain how the Creator revealed the healing properties of red willow bark. Traditional healers may be embedded in a tribal community, or they may be supported by tribal- and behavioral-health divisions. Sometimes, they are able to treat someone right away, but other cases may require the healer to orient themselves to the particular situation, including listening for guidance from the ancestors. Often, the healers will offer a diagnosis and prescription of lifestyle adjustment, change, prayer, or contemplation in an effort to help the patient more effectively balance the competing priorities in life.

This holistic life assessment is vital to the role of traditional healing in addressing historical and intergenerational trauma, as is attunement with one’s cultural heritage, language, and the wisdom of one’s ancestors. By addressing the disconnection caused by removal and assimilation, these methods heal wounds Western medicine is only beginning to acknowledge even exist. While simple, this is far from easy, and tribal leaders and health practitioners face many challenges in returning to traditional cultural ways.

The Trauma-Informed Leader

If tribal leaders understand the profound loss and negative outcomes caused by forced assimilation and cultural discontinuity, then they will be able to more effectively use traditional methods to confront the loss. Many trauma-informed elected tribal leaders have begun more openly discussing the matter of suicide, for example, although in some cultures it remains a sensitive matter to speak of the deceased. But preventing suicide requires discussing suicide. On this and many other topics, engaged policy makers must secure appropriate funding and tools to deal with the crises of suicide, addiction, and overdose.

The traditional seven grandfather teachings for some tribal communities of love, respect, bravery, wisdom, truth, honesty, and humility may inform how these difficult conversations can build capacity for understanding and healing (Waseyabek Development Company, n.d.). While not all tribal leaders are expected to be experts in everything, all who have care and compassion for their communities stand to benefit from their understanding of trauma-informed care.

Acivities:

Reflection Questions:

-

How do I keep myself regulated so that I can model self-regulation for my students?

-

What are the things that gave American Indian and Alaska Native people good health, wellness, and balance before contact?

-

When I restore cultural activities in my family, we experience …

Resources

Practices for Self-Care

Providers must have their needs met, too, if they are to serve AI/AN children and families. As the saying goes, “we cannot self-care our way out of systems of oppression.” Systemic change is required, which means we need to acknowledge our collective responsibility to ensure health and wellness in our communities.

But systemic change, although required, is slow. As that transformational work progresses, we must also build strong networks of providers and support staff to ensure that we confront the challenges together, as a community, instead of each trying to go it alone. Some tips for identifying and minimizing provider burnout are:

- Understand the symptoms of compassion fatigue and burnout

- Seek out support from colleagues or professionals

- Stay solution-focused (i.e., resist the urge to focus on past trauma(s) instead of on the possibility of healing)

- Create balance—give yourself permission to experience joy and to take breaks

- Lean into culture and ceremony

- Say no when you feel you don’t have the capacity to engage at the requested level

- Build or reconnect with community.

- Take care of your physical and mental health needs

- Look for opportunities that build hope

- Connect with nature

Resources

Compassion Fatigue: Can We Care Too Much (Administration for Children and Families)

Advocacy at the Community Level

“In the end, the only thing that is going to make the change is when we go back to our culture. In good community prevention plans, they all go back to whatever the culture is.”

– Anna Whiting Sorrell, MPA (Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes)

Advocacy for the necessary systemic change occurs at every level, from the individual, to the neighborhood, to the community, to national initiatives such as the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, announced in 2021 by Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland (DOI, 2021). On a local scale, efforts include advocating for the return of ancestral remains, as was done by the Rosebud Sioux (Associated Press, 2021). Similar efforts have been championed by many Native tribes and organizations across the country.

These local efforts have been unified by the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, which has in turn created toolkits and resources to advocate for the U.S. Truth & Healing Commission Bill. Passing this bill would authorize a full inquiry into federal assimilation policies, identify the locations of children’s burial grounds at residential schools, consolidate relevant church and governmental records, provide for public hearings, and result in a final report, including concrete recommendations for reconciliation (U.S. Truth & Healing Commission Bill Advocacy Toolkit, n.d.).

As with many aspects of the boarding school atrocities, discussing how to advocate means confronting disturbing topics.

Call to Action: Community Leaders

Community leaders should engage with how the Indian boarding schools touch almost every aspect of modern life for AI/AN people. These actions can include sending out newsletters, passing resolutions to honor victims and survivors, hosting community events and observances, and creating spaces for healing.

Figure 15. Full waiting room at a Native health clinic

AI/AN tribal communities have long practiced community-based and traditional healing. As health care became increasingly tied to the Indian Health Services’ standards of care, however, traditional healing practices became deemphasized. That process, however, is beginning to reverse itself. Congress has authorized more flexible sorts of funding, so tribal nations are increasingly applying traditional healing practices to modern ailments under a self-governance approach. As tribes are at varying stages of cultural and traditional reclamation, these traditional practices may be applied to a wide range of physical, mental, emotional, social, and spiritual matters.

The 2015 Tribal Behavioral Health Agenda aimed to measure the impact of trauma-informed care and tradtional medicine on health outcomes (SAMHSA, 2016). Traditional practices and ceremonies are important sources of healing for many AI/AN people, despite the complex task of integrating them with modern practice. As researchers gain familiarity with a trauma-informed framework, however, new strategies have begun to emerge. Whatever the specific methods, any effective trauma-informed care begins with the reclamation of culture, language, and AI/AN ways of knowing.

One example of how an individual can help a community heal from boarding school trauma was shown at a high school in the Pacific Northwest. Nez Perce tribal member, Jayden Leighton, a high-school senior, successfully petitioned her school to host an Orange Shirt Night during a varsity volleyball game. Her team wore special orange jerseys for the match, at which spectators were able to learn about the impacts of the Indian boarding schools.

“She is so brave and passionate,” said Jayden’s mother, Teresa. “She planned that whole event by herself—her teammates helped her to decorate the gym, and I made the flyer, but she took the initiative to get the t-shirt design, sponsor, and to sing an honor song and lead a moment of silence.” Community leaders do not have to be professionally trained, or even adults—we all can make a difference. What matters is being informed, passionate, and committed.

Some dates to consider incorporating Indian boarding school awareness activities include:

- National Missing and Murdered Indigenous Peoples Day, May 5

- Yellow Ribbon Week, the week of September 9

- World Suicide Prevention Day, September 10

- National Day for Truth and Reconciliation (also known as Orange Shirt Day), September 30

- Indigenous Peoples Day, Second Monday in October

- Red Ribbon Week, October 23–31

- Native American Heritage Month, the month of November

Activity

Reflection questions:

- Do I focus on individuals or the community? Why is this my focus?

- How do I engage with my neighbors and community?

- Who is in my community? Is it intergenerational, diverse, healthy?

- Who do I wish was in my community, and what steps can I take to get there?

- When I create sacred spaces for ourselves, our families, and our communities we …

- Using our strengths, my community can create …